Your average American

Part One of a three part series

When supper was finished at the Marker home, Alex would sit back in his chair and start telling stories.

“Our kids loved hearing his stories,” Alex’s daughter-in-law Carolee Marker said. Her children, Michael and Tamy, would listen intently to their granddad telling stories of his childhood.

Years later the stories are still vivid in the minds of the hearers, but the same cannot be said for the story teller, Alex Marker.

Born on Sept. 3, 1910, Alex is the son of German-Russian immigrants George and Mollie Schindler Marker.

“When he was small he was ornery,” Caroleen said. “He would fight anyone who would call him a Russian. He probably still would today, if he could.”

Alex was an “American,” from German descent, not a Russian.

His parents put him in a German school, but he hated every minute of his time there. He told his parents he wanted to go to “American” (public) school.

Almost every day young Alex would get a spanking.

It wasn’t that Alex didn’t want to learn, he just didn’t like the school. He wanted to go to an “American” school. So finally, his parents gave in to his requests and allowed the young “American” to attend public school.

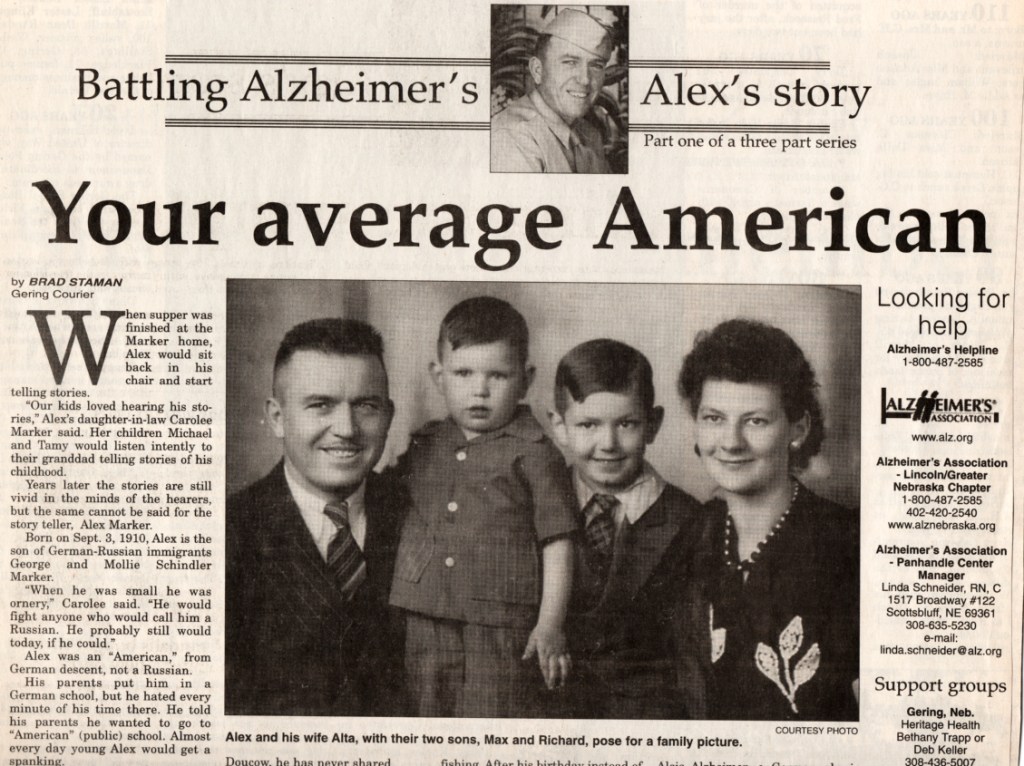

On Feb. 20, 1937, the proud American married Alta Weber.

The young couple made a home for themselves in the Scottsbluff area. Alex worked hard providing for them and after his father passed away his mother moved in with them.

In the house they would speak German.

At the age of 32, with a wife and two sons, Alex was drafted into the army. A war was raging in the home of his ancestors. With his German heritage and a good understanding of the language, Alex became an interrupter.

On the front lines he was one of the first into enemy territory. He was one of the first soldiers to enter the concentration camp at Doucow.

After returning home the story teller didn’t share his war stories. He held those stories to himself, until recently. The stories of Doucox, he has never shared.

Upon returning home he went back to work, For some 37 years Alex worked as a butcher for Swift in Gering.

On Aug. 2, 1957, his oldest son, Richard married Carolee Reading. In 1965, Alex and Alta’s youngest son, Mar, married Jacque Wells. His first grandchild, Tamy, arrived on Dec 8, 1958. She was the first of five grandkids, 11 great grandchildren and five great-great grandchildren and a sixth one is on the way.

Between work, telling stories and fishing, Alex would make furniture and other woodworking projects. Swinging baby cradles can be found today in the homes of family members.

He stayed active building swings and other furniture for his grand-children until his 80th birthday.

When Alex turned 80 he decided he didn’t have to do anything anymore and he stopped doing everything.

Before his 80th birthday, Alta would stay home when Alex went fishing. After his birthday instead of heading out before the sun rose, Alex would often wait until afternoon and then “con” Alta into going with him. Once they’d reach the fishing hole, Alta would wait in the car, patiently crocheting, while Alex fished.

The story teller also began to repeat his stories, telling those around him the same story over and over and over again.

“I know,” Alex would say, then he’d tell the same story again.

“At first it was aggravating to have to listen to the same story over and over,” Carolee said. “You wanted to say, ‘Come on grandpa, you just said that.’ But you didn’t.”

Richard and Carolee decided they would move to Gering from Potter in 1997, to help care for their parents.

Alta suffered from osteophsroes and was very frail, but like her husband, she was proud and problems where seldom talked about.

One day, however, Carolee found a small booklet while visiting her mother-in-law. The booklet was about a progressive, degenerative disease that attacks the brain know as Alzheimer’s.

The disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German phsyican, who first described the disease in 1906, Alzheimer’s Association Panhandle Center Manager Linda Schneider said. Symptoms include memory loss, decline in the ability to perform routine tasks, disorientation, difficulty in learning, loss of language skills, impairment of judgement and personality changes.

No one really knows what causes the disease and there is no cure.

There are “currently four million Americans battling with Alzheimer’s disease,” Schneider added. In Scotts Bluff County there are over 950 people effected by Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder.

In the past Alzheimer’s was a hidden disease.

“It was OK to have something wrong with your legs or arms, but not with your mind,” she added.

Those feelings are still there, even with more and more information available about the disease.

Holding the small booklet Carolee asked, “Where did you get this?”

“I don’t remember,” Alta answered. “But I want you to take it home and read it. I might need your help.”

Struggling to remember

Part two of a three part series

The bad stories, those that reveal problems weren’t shared in the Marker home. They were kept to one’s self, not even shared with Alex and Alta Marker’s children or grandchildren.

“You didn’t say anything was wrong,” Alex’s daughter-in-law Carolee Marker said. “It seems to be ingrained n our heritage.”

“Take care of it yourself, is the thought,” Tammy Sauers, Beverly Healthcare’s Alzheimer’s Care Unit Director said. “It is very common” when it comes to dealing with a disease that affects the mind.

Alex Marker was dealing with just that. Though no one was saying it, in private or public, Alex had Alzheimer’s.

During the early stages of Alzheimer’s one may being to repeat themselves, Tammy said.

“You might go to their refrigerator and find a shoe next to the milk,” she said. “They may have trouble caring for themselves or have trouble finding their way home.”

Throughout Alex’s life had told stories. Stories of his childhood, but the stories of his struggles to remember some of the simple things weren’t being told, even by Alta.

One story stayed hidden until a week before Alex was to appear before the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Alta pulled Carolee off to the side one day and told her she need her help. Alex had been pulled over by the police and shed need Carolee’s help in gathering all the paperwork for his court appearance.

As Alta shared the story, Carolee learned that one evening Alex and Alta had gone to supper at Grampy’s (present day Whiskey Creek).

On the way home Alex turned down the wrong street.

“This is not the right road,” Alta said.

“Yes it is!”

“No it is not!”

A heated argument ensued and for the next three hours the couple drove around the countryside, up one road, down into ditches, through Minatare and finally back into Scottsbluff. Driving down the Scottsbluff/Gering highway, someone called the police.

“There’s a car driving down the middle of the road,” the caller told police.

A police officer pulled Alex over in the Alco parking lot.

Asked to get out of his car, Alex had words with the officer.

“I will not take your keys tonight,” the officer said, “but I will follow you home and you will need to appear in court.”

Alex was losing his independence and “a man like Alex isn’t going to give up without a fight,” Tammy said.

“He was frustrated,” Tammy said. It is common. “There is a lot of anger with this disease.”

The day Alex was to appear in court he was going to “tell that officer a thing or two.”

“We (Alta and I) were scared to death he was going to do just that,” Carolee said.

In court there was no incident. Alex lost his license, but he controlled his anger.

The driving incident is a common problem for Alzheimer’s patients.

“They can leave home to go for a walk or drive (day or night) and not remember how to get home,” Alzheimer’s Association Panhandle Center Manager Linda Schneider said.

Patients have been involved in car wrecks, lost for days and even died of exposer due to bad weather because they simply can’t remember how to get home.

A program called Safe Return, sponsored by the Alzheimer’s Association provides patients with an identification bracelet, labels for their clothing and a card for their wallet. When someone finds them there is a number they can call and the person can be taken safely home.

Behind closed doors, Alta cared for Alex. Even though she was struggling with osteoporosis she “wasn’t going to give him up,” Carolee said.

Alta, like so many caregivers, over compensated, putting her own health at risk to care for her husband of 62 years.

Although Alta was frail, her mind was strong, Carolee said. Alex was struggling with his mind, but his body was strong. Together the two seemed to be able to manage. Until one day, tow-and-a-half years ago, Alta fell and broke her hip.

Preparing her for surgery, she passed away.

Alex came to stay with his son, Richard, and his wife, Carolee.

The first night, Alex was in bed in his room. Down the hall, Richard and Carolee were in their bed. All of a sudden the light came on.

Alex was standing in the door.

“I’m sorry,” he said, as he turned the light off and walked toward the back door.

When he reached the back door, he unlocked it, opened the door, closed the door, locked the door and moved on.

“What is he doing?” Carolee asked Richard.

“I don’t know,” Richard replied.

Alex moved from room to room, opening and closing doors.

“At first we thought he was just checking to make sure everything was safe,” Carolee said But every night the same routine would take place.

“It’s called Sundowning,” Tammy said, “and it’s very common.

When it starts to get dark, some patients with Alzheimer’s will become like a caged animal. They will have to get up and begin looking for something.

Richard and Carolee began taking turns staying up nights to keep an eye on Alex. Richard’s brother, mas and his wife Jacque also took turns staying up with Alex.

As long as one of them stayed awake with him, it was OK. But if they would close their eyes, Alex would get up and start walking again.

The majority of those with Alzheimer’s are receiving home car, Linda said. They caregiver is a spouse, a family member or a professional caregiver. There are also some residential facilities equipped to care to Alzheimer’s patients.

“Caregivers put in a 36 hour day,” Linda added.

At home, Alex wouldn’t bath or change clothes for days. Carolee, Richard, Max and Jacque were struggling to provide the care Alex needed.

They decided to look into Beverly Healthcare.

“In order to make the transition easier we try to encourage residents to come with loved ones for a meal, maybe try that for a couple days,” Tammy said. So Alex, his sons and their wives visited.

Walking through the halls, Alex saw people he knew. Going past one lady in the all, Alex stopped turned to her, called her by name and began a conversation.

“How do you know me?,” the lady asked.

She turned out to be Alex’s sister’s best friend in school.

Alzheimer’s patients lose the short term memory first, Linda said. The long term can be very acute.

Though it was one of the hardest decisions they ever had to make, the Markers decided it would be best for Alex if he moved to Beverly Healthcare.

The next day, when it came time to go, Alex sat down in a chair in his son’s living room and refused to go.

Fighting a losing battle

Part three of a three part series

Sitting in room 100 at Beverly Healthcare, Alex Marker points to the coffee table. “I built that,” he said. “I built that end table.”

Furniture that Alex has built can be found in the homes of his two sons, Richard and Max, many of his grandchildren’s homes and in the homes of his great-grandchildren. But the furniture in room 100 was not built by Alex, but no one corrects him.

“Alex tells the darndest stories,” Tammy Sauers, Beverly Healthcare Alzheimer’s Care Unit Director said. “He is such a sweet man.”

Many of Alex’s stories are gone, stolen from him by Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease affecting the mind that leads to problems with thinking, remembering, reasoning and judgement, Alzheimer’s Association Panhandle Center Manager Linda Schneider said. The disease impacts over four million Americans.

Being one of the four million doesn’t make it any easier for Alex’s family.

“Parents deserve to be cared for,” Carolee Marker, Alex’s daughter-in-law, said.

When family found out they couldn’t care for Alex on their own they moved him into Beverly Healthcare’s Alzheimer’s facility.

“That was the hardest decision we’ve made in our life,” Carolee said.

When Alex first moved into Beverly Healthcare he would say, “Take me home. I want to go home.”

Then he started asking, “Is this where I live?”

“You sold your house,” Carolee would tell him.

“Oh, that’s right,” Alex would say.

Walking from the front door at Beverly Healthcare down the hallway to his room, he will sometimes say, “Mom loved this hallway.”

“Alex lives much younger than he really is,” Tammy said. “Ask him today how old he is and he will tell you he’s somewhere between four and 17. Tell him he’s 91-years-old (which he is) and Alex looks at you like your from Mars.”

“He lives younger than we are,” Carolee said.

Often he doesn’t recognize Richard or Carolee. He is too young to have kids, they are just nice people who come to visit.

“The old man (Richard) came to take me for a walk,” Alex will say.

He tells Tammy his family never visits him, but they visit almost everyday. However, they are not the family he is looking for. Family, to Alex, is his mother and sister.

“What did I do so bad that mom left me here?” Alex has asked Carolee.

Moving Alex into Beverly Healthcare was not easy.

When the day came to move in Alex sat in Richard and Carolee’s living room and refused to go. Richard and Max had to convince their father to make the move.

“It was an awful transition,” Tammy admits. “Transitions are usual very hard.”

Alex’s was harder than most, she added.

The first night Alex fell. Medication, which Tammy said they try to avoid using , was needed.

The next morning Alex looked terrible. His face was all swollen.

“We’re taking him home,” Carolee said. But Richard was strong, that day. Though it was tough, staying was best for Alex.

From Alex’s point of view, “I don’t think he knew what was going on,” Carolee said.

Alex is now in the later stages of Alzheimer’s.

Many different staging systems exist, including a three-stage and a four-stage, two seven-stage scales and a 16-stage scale. The three-stage is most often used by the Alzheimer’s Association.

Stage one (early) can last two to four years. In this stage cognitive changes are very subtle. There can be memory loss, especially recent events and new information. There can also be changes in emotions and feelings. The diagnosis is seldom made at this point.

The second stage (middle) can last two to 12 years. Diagnosis is usually made in this stage. There is obvious defects in memory, retention and recall. There may be some muscular twitching and they may be intolerant to cold. The second stage is a time of loss and grief for family members.

The third stage (late) can last one to three years. They person is unable to perform purposeful movements and does not recognize others, including family.

“As the disease progresses,” Linda said, “the memory goes backwards.”

Every patient with Alzheimer’s progresses at a different rate, but it is fatal. Some people will progress very quickly. Others, like Alex, progress slower.

The progression from when symptoms first appear to death can take anywhere from three to 20 years, Linda said.

Presently, there are a number of research projects taking place around the country.

“Hopefully we’ll find a cure or something to prevent it,” Linda added. “If we don’t the number of people with Alzheimer’s will triple in the next 40-50 years.”

Alex’s physical health is good. He loves ice cream, going for drives in the car and walks.

“Sometimes he thinks he’s in the army,” Carolee said

“He will sing his army songs,” Tammy added.

“We’re in the army now, we’re not behind the plow . . .,” Alex will sing.

The old soldier, the strong German-Russian who worked hard throughout his life will lose his battle with Alzheimer’s. He will continue to to have his stories stolen from him. His ability to walk will be stolen, as will his ability to feed himself. In the end Alzheimer’s will steal his life.

But today is a good day.

“You’re my son, aren’t you?” Alex asks Richard as they walk along the street outside Beverly Healthcare.

“Yes I am,” Richard answers.

Thanks to Alzheimer’s you never know what the day will bring. Today is good, tomorrow may be bad, but in the end there will be no happy ending to Alex’s story.